Phylum Press Mission Statement

In one sense Nancy and I felt we had a place in what is a long and rich tradition, both in terms of “pamphleteering,” and in literary cultural production. A glance at Granary Books’ A Secret Location on the Lower East Side or their Angel Hair Anthology (I especially am touched by the double forward to the latter by Lewis Warsh and Anne Waldman) gives ample testimony that there have long been editors and poets doing similar things. We need only point to Whitman’s self-publishing and Dickinson’s fascicles to see the roots of this history. But really the final catalyst was encountering the work of Simon Cutts, Erica Van Horn, and Coracle Press. The commitment evidenced by and as those productions provided us with the imagination of what was possible if one thought alternatively to producing mainstream books.

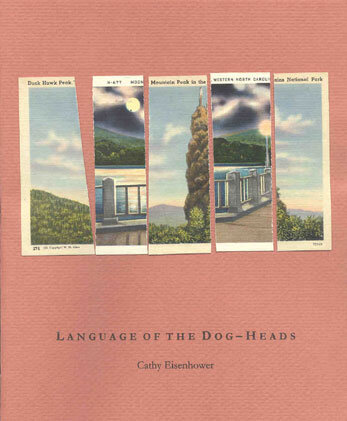

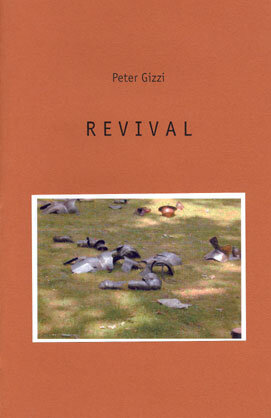

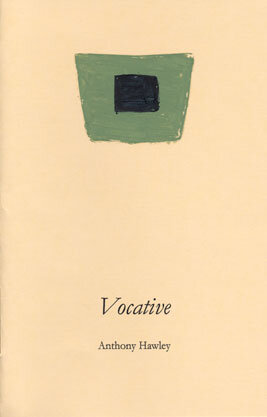

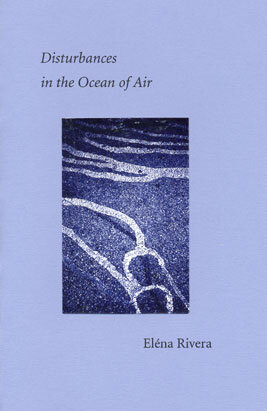

At the beginning we were motivated by what we perceived to be a lack. There seems to be ample (all things being relative of course) outlets or venues for those who are “mainstream” as well as for those who are dogmatically experimental. We felt that there were far fewer houses that were participating in the kind of work we most value. We think Roberto Tejada and Peter Gizzi to be prime examples of this aesthetic that we find compelling—that is, poets who are revisiting in vastly different ways the questions of lyric subjectivity after the various problematics have been brought to light. The writers we publish are (relatively) young and fugitive. We’re reluctant to describe precisely what our poetics might be, reluctant to suggest a particular school. Instead, we see ourselves as suggesting certain elective affinities among poets who are pursuing lyric poetry as a text of negotiations, whether the negotiations be with self, history, or culture, or something else entirely. This is less a school or movement than a sensibility I suppose.

We decided on chapbooks first because we could afford to produce them, simply put. We started doing pamphlets because Tejada’s book hit some production snags, mainly due to the logistics of the covers, which were designed and produced by an artist living in Mexico City. In the meantime because I’m a protestant from New England (“my culture did this to me”) I got anxious. We then decided to do a few pamphlets that we could put together very cheaply to be handed out at readings or mailed to friends and other writers. We liked the subversive idea of it all.

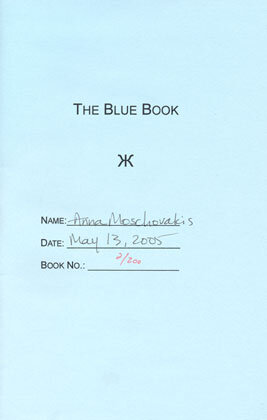

Strangely enough people seem to really respond to the pamphlets. We had always intended on getting ISBN numbers and getting them marketed on Small Press Distribution. I insisted however that the poet would sign every copy of every book. I’d been bothered for a while by the strange alienation of poetry production. We really do believe that poetry is a gift economy—and beyond that it makes possible a sort of community at least in the sense of elective affinities. Because of that I had to ask myself if poetry isn’t really capitalist, why was it still so often participating in the market economy model? There are precious few bookstores that would sell chapbooks, and those that do don’t sell many of them. Chapbooks at Grolier’s in Cambridge, MA may just as well not even be in the store. The other alternative would be to get distributed by SPD. That’s when it struck me that even SPD is of course just another commodity driven market in which one has to perform in such a way to be granted SPD’s legitimacy. All for the books to lie around. Too often have I seen even small, independent publishers (including those that claim to be alternative) publish work simply because it would sell. Or for the small press the most insidious development of all—contests. Even getting not-for-profit status is tricky and often should involve a lawyer and again costs a great deal of money. Worst of all, as Keith and Rosmarie Waldrop of Burning Deck advised us the application materials have to give the appearance that the press has hopes of someday becoming commercially viable.

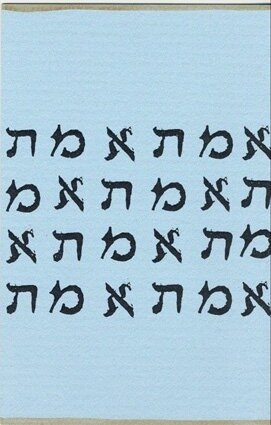

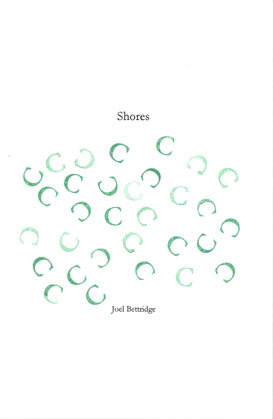

Thus we put our money and belief into every single book. And we like that we’ve struck a balance between an artist book, which is often rarefied and “untouchable,” and the standard poetry book. These are meant to be read. We have touched every single book, as have the authors—what clearer indication of our personal and social investment into a community of aesthetics? And what we receive back is conversation—participation in a network of thinking about poetry. And of course paradoxically our efforts don’t carry the legitimacy or authority of Knopf. Ah well, we do what we can. And perhaps all of this is naïve. I hope that’s it more usefully idealistic than naïve, but even so I think that’s only decided in comparison to the mores of the market economy that demands a particular brand of savviness.

As we’re committed to the belief that poetry is a gift economy, we’ve never sold a copy of any of our books, virtually all of which are out of print. In trying to avoid complete complicity in the usual capitalist paradigms, we seek out alternative distribution, i.e. usually we pay for our publications out of our own pockets and then give them away.

We hope that you enjoy these books. Please let us know what you think.

— Richard Deming, Editor

Summer 2003